Stopping Stealing American Jobs, Something Conservatives and Labor Unions Can Agree On...

For a PDF version of this fact sheet, click here.

The United States guest worker visa programs for skilled workers are a flashpoint in the immigration debate. Chief among the controversial skilled visa programs are the H-1B and L-1. The controversy is not surprising considering that nearly 400,000 guest workers receive work authorization through the H-1B and L-1 visas every year.

Temporary work visa laws do not have provisions to protect guest workers or American workers. Guest workers are paid below market wages, have little bargaining power, and cannot easily switch employers. The laws governing skilled worker visas allow for U.S. citizens and permanent residents to be replaced by guest workers. Despite increased and well documented abuses of temporary guest worker programs, proponents seek to expand guest worker programs without reforms.

This fact sheet explores the availability of guest worker visas and programs, provides an overview of the guest worker workforce, and explores the consequences of the programs for foreign and domestic workers.

What are Guest Worker Visas?

Guest worker visas, including the H-1B and L-1, allow citizens of foreign countries to temporarily work in the U.S. OPT, while not a visa, grants temporary work authorization for foreign citizens who attend or graduated from a U.S. university.

The H-1B Visa

- An H-1B visa is a non-immigrant visa for a guest worker who will be employed temporarily in a specialty occupation or field.1 The visa is held by the employer, not the worker.[2]

- A “non-immigrant” is a person who enters the U.S. for a temporary stay.

- “Specialty occupations” are defined by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) as occupations which require the “theoretical and practical application of a body of specialized knowledge along with at least a bachelor’s degree or its equivalent.”3

- H-1B visas are issued for workers in a wide range of occupations, including computer-related occupations; architecture; engineering; education (pre-k through post-secondary); administration; medicine and health; management; life sciences; mathematics and physical sciences; social sciences; art; law and jurisprudence; writing; and entertainment and recreation.4 However, most visas, nearly 65 percent in FY 2014, go to employers hiring workers in computer-related occupations.5

- The H-1B visa is issued for three years and can be renewed for another three years.6 If the H-1B beneficiary’s employer sponsors the worker for a green card (permanent residence), then the H-1B visa can be extended in one-year increments until the green card is issued.7

- There is an annual cap on the number of H-1Bs that can be issued. The cap is 65,000 workers per fiscal year.[8] However, there are several exceptions, which raises the number of visas issued to over 120,000 each year.

- There are 20,000 H-1Bs available for workers holding a master’s degree or higher from an American institution of higher education.9

- Nonprofits and government organizations that conduct research and institutions of higher education are exempt from the annual cap.10

- The cap does not apply to renewed applications.11

- There are 6,800 visas set aside within the cap under the terms of the U.S.—Chile and U.S.—Singapore free trade agreements and unused visas are made available for use in the next fiscal year.

H-1Bs Available Under Fixed Cap

|

H-1Bs Available to Workers with a Master’s Degree or Higher from an American Institute of Higher Education

|

H-1Bs Available to Institutions of Higher Education and Nonprofit and Government Research Organizations

|

| 65,000 | 20,000 | Unlimited* |

* In FY 2014, nearly 40,000 initial employment visas were issued in the “unlimited” category.

12

- An H-1B beneficiary must either have a bachelor’s degree or higher (from a U.S. or foreign institution), have a state license or certification that permits practice in the specialty occupation, or have training or experience (with progressively responsible positions) in the specialty occupation that is equivalent to completion of a degree.13

- H-1B employers are not required to show that there is a shortage of U.S. workers. H-1B employers must only attest: (1) “that they will pay H-1B workers the amount they pay other employees with similar experience and qualifications or the prevailing wage; (2) that the employment of H-1B workers will not adversely affect the working conditions of U.S. workers similarly employed; (3) that no strike or lockout exists in the occupational classification at the place of employment; and (4) that the employer has notified employees at the place of employment of the intent to employ H-1B workers.”[14]

- The requirements for H-1B “dependent employers” and “willful violators” are slightly different (more about these employers below). These employers must attest: (1) “that they did not displace a U.S. worker within the period of 90 days before and 90 days after filing a petition for an H-1B worker; (2) that they took good-faith steps prior to filing the H-1B application to recruit U.S. workers” and “offered the job to any [U.S.] worker who applies and is equally or better qualified for the job” than an H-1B worker; and (3) that in the event the worker is placed with a third-party employer, the original employer inquired with the third-party employer that it did not displace or intend to displace a U.S. worker within the 90 days before and 90 days after the placement.15

The L-1 Visa

The L-1 visa is used to transfer employees of multinational corporations who have been employed by the company abroad to a branch, parent, affiliate, or subsidiary of that same employer in the U.S. The L-1 visa beneficiary must have been employed by the company within the three preceding years and have been employed abroad by the sponsoring firm continuously for one year.

[16] There are two classes, the L-1A visa is for managers and executives and the L-1B visa is for workers with “specialized knowledge.”

[17] Also, the L-2 visa grants employment authorization for the spouses of L-1 visa beneficiaries.

- The L-1 visa is often used by companies to facilitate “knowledge transfer,” which means enabling guest workers to come to the U.S. and then take the knowledge and skills they learned in the U.S. to their home country.[18] For example, Intel uses the L-1 visa so American workers can “train L-1 workers who staff the company’s offices in Russia, India, China and other high-growth markets.”[19]

- As with the H-1B visa, the L-1 visa is held by the employer, not the worker.[20] There is no cap on the number of L-1 visas that may be issued. The visa is renewable for up to six years for specialty workers and seven years for managers[21] and there is no wage minimum.[22].

- A worker who comes to the U.S. on an L-1 visa can be sponsored by the employer for permanent U.S. citizenship, but very few receive sponsorship (about 5,000 in FY 2014 were sponsored for citizenship).[23]

Optional Practical Training Program

The Optional Practical Training (OPT) program allows students on an F or M visa to work for 12 months after graduation and students with a degree in a science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) field to work another 17 months for a total of 29 months. OPT does not have a wage requirement and employers are not required to pay Medicare or Social Security taxes for OPT beneficiaries.

[24] The OPT program does not require that employers test the labor market before hiring an OPT beneficiary.

B-1 in Lieu of H-1B

Finally, the B-1 visa in lieu of H-1B allows employers to bring in workers even when the cap for H-1B workers has been reached. The B-1 in lieu of H beneficiary must have a bachelor’s degree, perform work or receive training of an H-1B caliber (specialty work), be paid by their foreign employer (cannot be a U.S. source), and the task they are coming to America to do can be accomplished in a short amount of time.

[25] There is no information available on how many of these visas are issued each year, their...

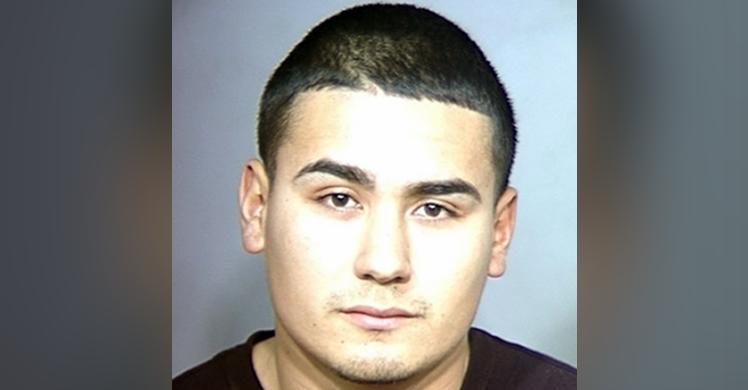

In his seventh year of “fundamentally transforming the United States of America,” as Barack Obama memorably promised five days before he was elected president, we’re learning new details about thousands of immigrants who were released from custody after being convicted of serious, violent felonies and horrific sex crimes. Instead of doing his duty to keep bad people out of America (or remove them if they manage to sneak in), Obama is bringing us even more diversity by accepting thousands of refugees from terrorist-harboring countries such as Syria and Somalia.

In his seventh year of “fundamentally transforming the United States of America,” as Barack Obama memorably promised five days before he was elected president, we’re learning new details about thousands of immigrants who were released from custody after being convicted of serious, violent felonies and horrific sex crimes. Instead of doing his duty to keep bad people out of America (or remove them if they manage to sneak in), Obama is bringing us even more diversity by accepting thousands of refugees from terrorist-harboring countries such as Syria and Somalia.