|

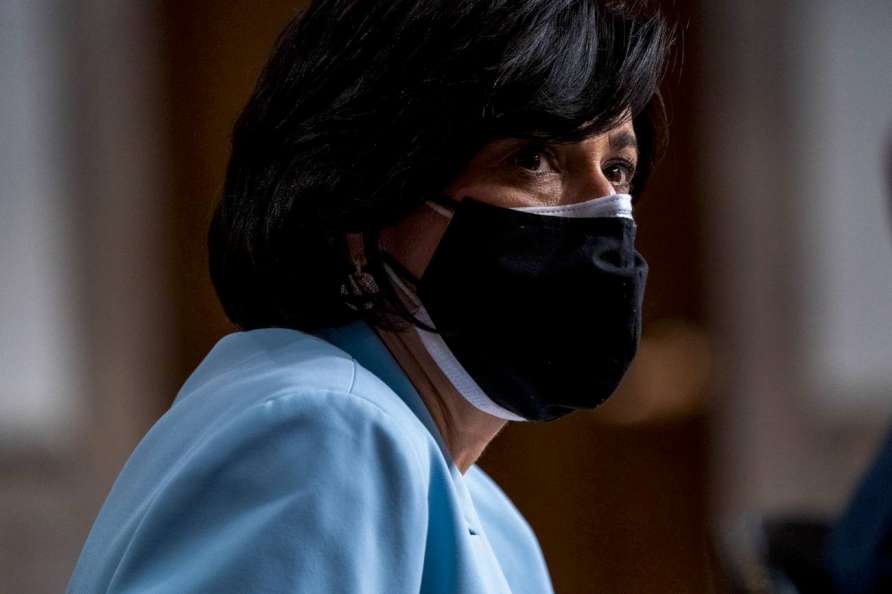

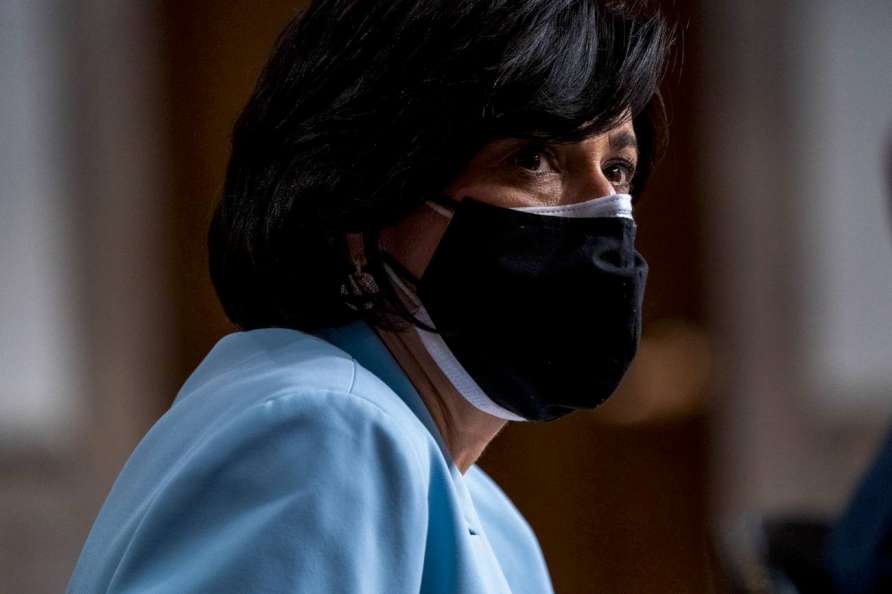

| Filthy Liar: Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, |

Mass youth hospitalizations, COVID-induced diabetes, and other myths from the brave new world of science as political propaganda

The main federal agency guiding America’s pandemic policy is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which sets widely adopted policies on masking, vaccination, distancing, and other mitigation efforts to slow the spread of COVID and ensure the virus is less morbid when it leads to infection. The CDC is, in part, a scientific agency—they use facts and principles of science to guide policy—but they are also fundamentally a political agency: The director is appointed by the president of the United States, and the CDC’s guidance often balances public health and welfare with other priorities of the executive branch.

Throughout this pandemic, the CDC has been a poor steward of that balance, pushing a series of scientific results that are severely deficient. This research is plagued with classic errors and biases, and does not support the press-released conclusions that often follow. In all cases, the papers are uniquely timed to further political goals and objectives; as such, these papers appear more as propaganda than as science. The CDC’s use of this technique has severely damaged their reputation and helped lead to a growing divide in trust in science by political party. Science now risks entering a death spiral in which it will increasingly fragment into subsidiary verticals of political parties. As a society, we cannot afford to allow this to occur. Impartial, honest appraisal is needed now more than ever, but it is unclear how we can achieve it.

In November 2020, a CDC study sought to prove that mask mandates slowed the spread of the coronavirus. The study found that counties in Kansas which implemented mask mandates saw COVID case rates start to fall (light blue below), while counties that did not saw rates continue to climb (dark blue):

CDC.GOVThe data scientist Youyang Gu immediately noted that locales with more rapid rise would be more likely to implement a mandate, and thus one would expect cases to fall more in such locations independent of masking, as people’s behavior naturally changes when risk escalates. Gu zoomed out on the same data and considered a longer horizon, and the results were enlightening: It appeared as if all counties did the same whether they masked or not:YOUYANG GUThe CDC had merely shown a tiny favorable section, depicted in the red circle above, but the subsequent pandemic waves dwarf their results. In short, the CDC’s study was not capable of proving anything and was highly misleading, but it served the policy goal of encouraging cloth mask mandates.When it comes to promoting mask mandates in school, in October 2021 the CDC famously offered a comparison of masked and unmasked schools in Arizona’s Pima and Maricopa counties in their own journal, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). The analysis claimed that schools with no mask requirement were 3.5 times more likely to experience a COVID outbreak when compared with schools that mandated masking. But the analysis did not adjust for rates of vaccination among either teachers or students. The paper also looked at two counties in Arizona with different political preferences, and thus did not separate mask mandates from other patterns of behavior that fall within partisan lines. Democratic voters, for example, are much more likely to embrace mask mandates and are more likely to otherwise curtail their behavior as they report greater overall concern about COVID. Elementary schoolchildren generally do better with COVID than high school kids, but the CDC’s analysis lumped all ages together, and might have been biased by the fact that mask mandates were more common at ages when outbreak detection occurs less often.These were only a few of the CDC paper’s problems. When the reporter David Zweig investigated it for The Atlantic, he found that the exposure times varied: The mask mandate schools were open for fewer hours per day, with less time for outbreaks to occur. Zweig also found that the number of schools included did not add up. He hypothesized that some schools conducting remote learning might have been wrongly included, but when he asked the paper’s authors to provide him a list of the schools, they didn’t. In short, the more one examined this study, the more it fell apart.Masking is not the only matter in which the CDC’s stated policy goal has coincided with very poor-quality science that was, coincidentally, published in their own journal. Consider the case of vaccination for kids between the ages of 5 and 11. COVID vaccination in this age group has stalled, which runs counter to the CDC’s goal of maximum vaccination. Interestingly, vaccinating kids between 5 and 11 is disputed globally; Sweden recently elected not to vaccinate healthy kids in this age group, and some public health experts believe that it would be preferable for kids to gain immunity from...